In the Mojave Desert to the north of Los Angeles there are homeless people who have nowhere left to turn. Police in nearby City of Lancaster have been evicting and arresting people for the crime of being too poor to afford somewhere to live. Through the journalism of Sam Levin and the photography of Barbara Davidson, their story becomes a reality for people all over the world. The power of photography to reveal the human condition is undeniable.

Sitting in my home 15,000 miles away from LA County I am struck by two things. Firstly, how lucky I am to be worried about whether or not my mortgage will be fully paid off before I retire. At least I have a home. Secondly, how deeply important it is to connect with your subject.

theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jul/18/california-homelessness-crisis-mojave-desert

It sounds bleeding obvious doesn’t it? Maybe we hear it so often that we no longer hear it at all. The images presented in The Guardian story could, in theory, be captured by anyone. Camera technology is no limit to this kind of reportage. In reality they weren't taken by nearly most everybody. Nobody else got involved. Nobody else went there. Nobody else stepped up. Not only did Barbara Davidson go there, but she didn’t stand on the sidelines either. She got right in amongst it.

You can’t be a photographer and remain an innocent bystander. You have to take sides.

I love documentary as a genre. I also argue that there is no such thing as documentary however, not in the sense that “the camera never lies”. Everything is art. Documentary is art. I say this because art is expression, and great documentary is always about expressing a story. There is a story to be told, and the art is on the telling. Even if you decide you wont take sides, you already have.

When you pick up a camera and point in one direction instead of another, you are changing the narrative of the story. Do you capture the vast expanse of an empty desert, or do you capture the broken down RV ten miles from the nearest water? You have to take sides.

The challenge in documentary is twofold. Recognising your own influence on the story, and actually knowing enough about the story to document a point of view. You can't reveal what you don't know. Which brings us back to “connection”. What you know is based on your connection. Photography is about connection. How you connect to the people in your frame, how you connect to the landscape, or how you connect to the wildlife. Whatever your connection is, that's what the camera can reveal.

Imagine there’s an invisible piece of string between you and your subject, a string that tethers your attention and draws you closer. A string that keeps you in a clear line of sight and consciously focused. A string that connects you and the subject.

If you don’t have that tether then the photographic process loses direction. Why are you there taking photos? What is connecting you to that place? What is the story. Capturing a story in photos is a consequence, not a process. You can be fully aware of the story yet still fail to reveal the slightest detail of interest. It does take effort after all. Connection demands effort.

That depth of connection will give you a depth of position inside the story. Only from within can we reveal what matters. If your connection is shallow then expect the photographs to reveal just that. As a travel photographer my biggest hurdle is the depth of connection to my subjects. Too often it’s fleeting and fails to delve beneath the surface. Too often it’s the opposite of documentary.

When I travel to a place like Arctic Norway there is over a decade of experience between us. I feel like the landscape embraces me, and I definitely embrace it back. I know so many bends in the road, villages that you’ve never heard the name of, mountain peaks that overlook a snow covered beach, and a handful of places where I can get a cinnamon scroll on Wednesdays and Fridays.

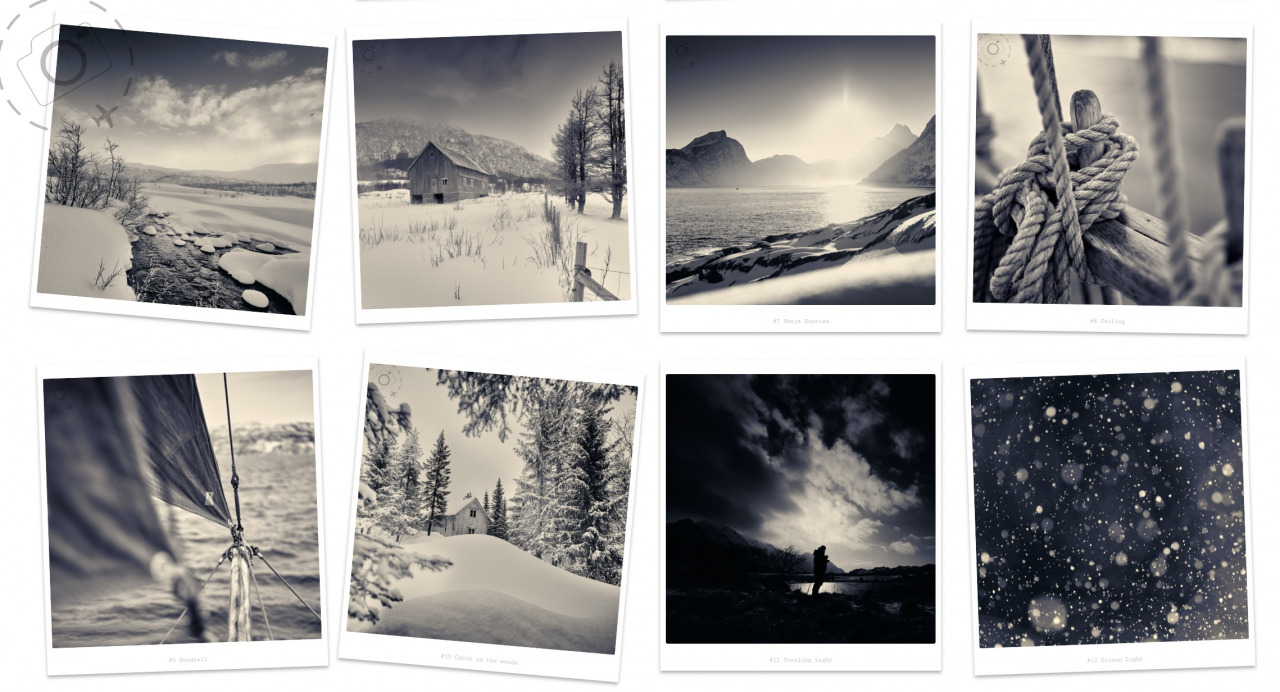

I did a series on Norway just before the pandemic which focused on the winter mood, and embraced the delight of life at 15 degrees below zero. Again, this was MY life below 15 degrees, which is different to the lives of so many others who live up there. This series was about my experience, not those of reindeer herders, or cod fishermen, or snow plough drivers.

https://ewenbell.com/editorial/The+North

There's a reason landscape photography is such a popular genre. It's a less confronting connection. Landscapes are relatively passive plus we get to pick and choose how and when we step into that space. Humans are far more complex for an introvert like me. Not that the ability to listen and observe isn't a valuable skill, because it definitely is. But it takes energy and confidence to connect with total strangers. More often than not I'm a little low on both.

Most of my work takes very tentative steps into other people's lives. It's largely commercial and focused on glossy enjoyments. I don't put myself into refugee camps, or homeless shelters, or war zones. I have shot exhibitions about elephant mahouts in Northern Thailand, conservation in Bhutan and the plight of orangutans in Borneo. They were luxuries every one of them, an almost indulgent expression of my connection to the wilds of Asia. They remain some of my best work. I hope there's time for me to do better though.

It can be very very difficult to connect with people, to crack open a gap and peer inside the lives of others. It demands patience and honesty. There is no camera upgrade or new technology to make it easier.

I envy those gregarious people who have a natural way with strangers, who never fall short of words and a conversation. By comparison I am awkward, stumbling and self-doubting. And I know it. But connections forged over time are stronger and deeper anyway. There are no shortcuts to quality.

On a micro level an awareness of connection is a powerful tool to drive your inspiration. Countless times I have sat down at a noodle stall in China and watched a lovely old lady prepare my meal. Steam rising from the pots and generous smiles to punctuate her conversation with family. This scene repeated itself dozens of times on every single trip. I would sit and observe and wait until the real photographic opportunity presents itself, typically once I was half way through my noodles. The act of sitting and watching is an underrated skill in photography. Not only do you become more comfortable with your subject, but they become more comfortable with you. Ideally you want them to be so comfortable they almost forget you are even there. That’s when the best photos happen.

On a macro level the goal is to put yourself out there and find new paths that lead you to something of substance, something that really matters to you. Connect with those communities in your world that matter. Take the camera with you and help other people to see that they matter too. I met a marvellous lady in Laos some years ago who was devoting her life to helping children learn to read, learn to write and learn to photograph. She was helping a generation of young Laos families to find their voice and share their stories. Why should I waste time trying to capture their stories when they could be telling their own? So I came back with a little sponsorship from Panasonic and a suitcase full of cameras.

The story of them telling their stories will forever remain one of my favourites. In a way I've made a career of helping other people to tell their stories, more than my own. That's ok though because the important thing is that they get told. With each telling the connections get stronger, in both directions.

Panasonic made a short video about the "My Library" project in Laos and it's marvellous and will bring a smile to your day. Have a watch!

Keep Reading

Join Ewen's newsletter for monthly updates on new photography articles and tour offers...Subscribe Here