[ A version of this post is available to watch on YouTube ]

Paint The Sky

On a very very dark night in Arctic Norway I find myself standing on a mountain pass, looking up at the northern lights as they dance above my head and out across the nearby fjord. Before starting a timelapse capture I take a test shot and make sure my focus and composition are in good order. I look down at the camera screen and... WOW. It makes me pause to suddenly see the rich red tones that outline the more visible green bands of aurora. That moment becomes far more exciting now that I can see those colours, even though most of them are visible only through the rear screen of my camera.

Some nights we have to wait very patiently for the auroras. They appear when they appear and not before. And even then, what you actually get to see will depend very very much on how close to the Aurora oval you are located. If you’re too far east or south from the aurora oval then maybe all you get to see is a soft glow on the distant horizon. When they are gentle it can be hard to tell if you’re seeing a band of cloud or an actual aurora. But, when they are powered by strong solar winds and dancing high above your head, there is no doubt at all. It’s really obvious and a wonderful sight for human eyes.

But what does the camera see in comparison to us? For sure, the camera will ALWAYS see more than our eyes can. Always.

On a good night they are bright and you can clearly see their familiar green hue with your own eyes. On a really good night you might see the red tones too. But, the light our eyes see is very different to what our cameras can assemble. The camera can pick up soooooo much more.

Experience vs Exposure

Seeing so many Aurora photos online these days really does create an expectation for people that can’t always be met. That’s what I really want people to appreciate before they make plans to visit the Arctic. Auroras are not only fickle and unpredictable, but they might be disappointing for you too. What you see on Instagram is NOT what you are going to see with your own eyes. Which doesn't mean it's not amazing, just that photos are usually much brighter and vibrant than in real life.

On a modest night with low level solar activity, I look at the shots taken on my cheap smart phone and they are dirty and dark and blurred. Maybe that’s a better indication of what we humans see – The worse your photography, the more accurate the photo is!

During a high level aurora event things are a little different. We often find ourselves just standing still and looking directly up to the night sky, marvelling at the motion and speed and light and colours and intricate patterns of ribbons and coronas. On nights like these, I let the timelapse mode on the camera keep working while I enjoy the motion and magic through my eyes.

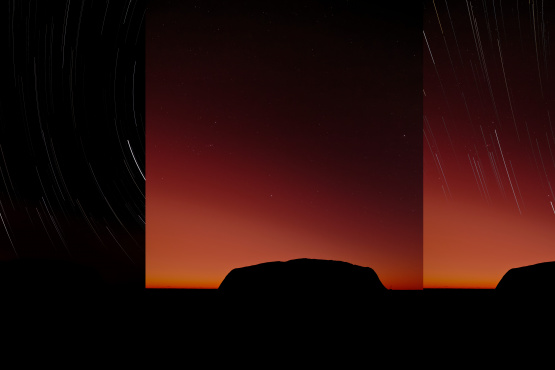

What I want to show you now is a rendering of an aurora, but degraded to give a sense of what the human eye sees in the night sky. For starters, the scene is much darker to our eyes as we struggle to pick up such low levels of light. We also struggle for contrast. Everything seems very flat compared to the pixel sharp rendering of a camera. And with low contrast comes low saturation. The colours are there, but difficult to discern until the brightest bursts come through. Red is especially elusive to identify.

What Our Eyes See:

Untouched RAW capture:

Processed and Optimised:

When we just stand are stare at the sky we can totally appreciate the magic of what’s happening up there. It’s still very very special, even if it’s not in Technicolor tones!

The thing is, even though our eyes see so much less than a camera does, the experience is still wonderful. Don't forget that our eyes are accustomed to seeing very little in the night, so suddenly having all this activity and even a hint of colour up there is genuinely impressive. We are suddenly deeply-immersed in that moment and our senses are filled to the brim. We only compute the spectacle as "dark or low contrast" when we compare our vision against the back of the camera. I think something extra happens inside our brains too. I think that our neurons rebuild an image in our memory that is somehow richer and more full of colours. We translate what our eyes see to be something closer to the photographic version. That's what the human brain does best anyway, translating little bits of sensory input and building a customised version of the world inside our heads.

Capturing photographs definitely changes the experience. In some ways it makes it better. We have a more vivid keepsake of the night. And it gives me a reason to stand out in the cold freeing my ears off for hours on end. Even on those quieter nights, when the aurora is low and slow, the camera can still pick out the colours our eyes struggle to see... and that can make for beautiful photography too.

Not The Same

But WHY does the image on the camera and the view through my eyes look so different?

The brightest auroras are roughly comparable to moonlight, which is right at the edge of useful light for most humans. We have evolved to do our best work in the day time. And that’s the nub of it. Humans just don’t see lower levels of light as clearly as our cameras do. With each generation of technology our cameras can produce higher quality and more pleasing images, with less and less light. Humans, however, don't get better with age!

There are three ways a camera can pick up auroras better than the human eye:

- High ISO on the camera

- Very slow exposures

- The timelapse effect

It’s not just the colours that get lifted by the sensitivity of camera sensors, but motion as well. When shooting timelapse we’re speeding up our perception of motion. We can turn 20 minutes of gentle movement into 20 seconds of rapid dancing.

The thing is, there really are times when the aurora moves fast. They really do ripple overhead and create ribbons... Sometimes. Indeed the problem on such evenings is that our cameras have usually been setup for slower exposures that give us a higher quality image, and then suddenly the exposures are overwhelmed by a more dynamic phase. So a timelapse you see posted to social media can give a very different impression to the experience of standing out there watching.

It is even possible to shoot video of aurora these days. You need silly high ISO and ideally a very fast lens, so these videos often look a little bit plastic or just strange, but it is possible. I don’t mind a poor quality video when it reveals those moments when auroras are dancing fast in real life.

Post Aurora

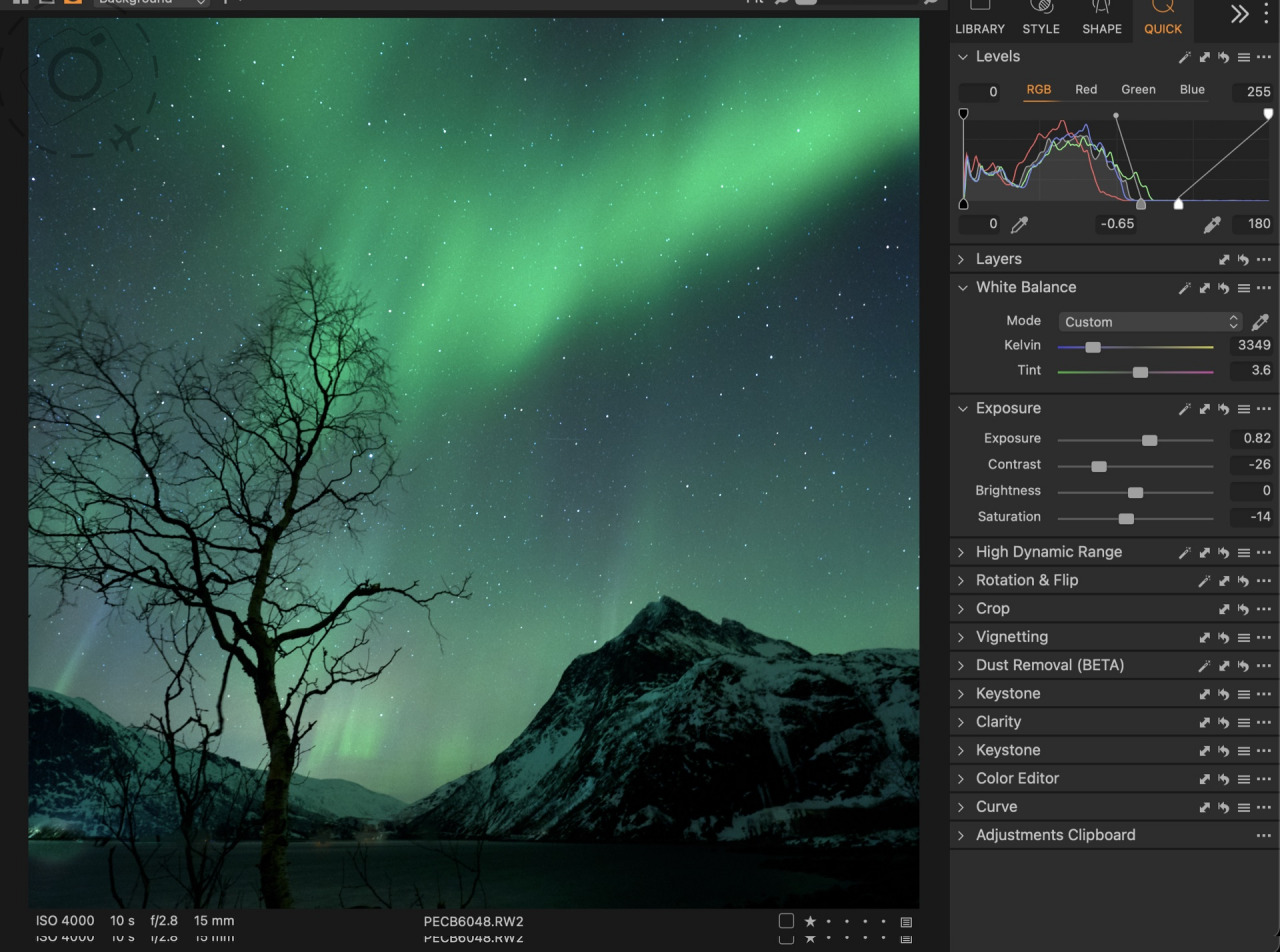

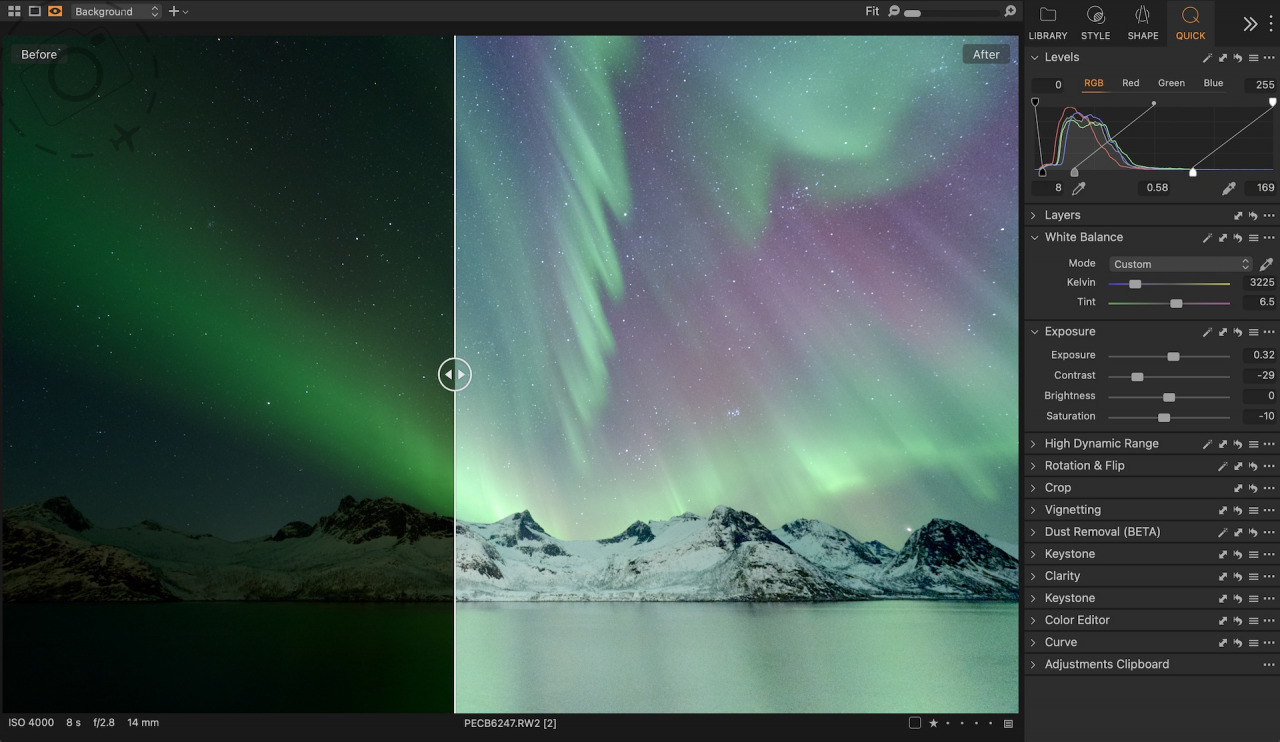

What do I do to my images to process the RAW files? Not much really. I’m relying on getting as much right in camera as possible The RAW file is only being tuned up a little. The real question with treatment of the RAW files is, “what STYLE do I want to present?”

Some people like to crank the saturation. Yikes. I think most people take it too far. And that’s one reason travellers often have crazy expectations when they arrive in the Arctic. They think they will see with their own eyes the same thing everyone is cranking in Photoshop.

Just a quick glance through thumbnails of aurora videos on YouTube will give you a good idea of what I mean by “over saturated”. It just looks awful, but that’s the problem with social media – the most extreme version of most things is often what gets the most attention. Same with the saturation dial.

I also think geography plays a part here too. If you’re NOT standing in Tromso on the night of a big aurora, and all you get are faint glows on the distant horizon, then you may not realise how far you’re distorting the image in order to try and match what folks are seeing elsewhere on the planet. You end up using post-processing to try and make your image match what you see on social media, which is a real trap.

I prefer to step back and go the other way. Step away from those crazy colours and keep it more subtle. I just prefer more natural and subdued tones. Which is easy for me to say when I’m up here in Tromso getting great shows of aurora.

I’m already getting rich colours because of the higher ISO ability of my camera, fast lenses and slow exposures. I’m starting with a beautiful scene anyway, there’s no need to amp it up further.

Keep It Real

Cameras and the human eye do see auroras differently. That doesn’t mean the camera is distorting the moment. Sometimes the photographer is distorting things with the saturation slider, but the camera is just doing what the camera does. It’s collecting light as best it can and rendering that into an image. This isn’t like an AI thing! Cameras are collecting actual light that really is there, it’s just that they do it so much better than our human eyes.

Many times I’ve been enjoying a great aurora night while my camera is shooting in timelapse mode, and then look down to be surprised by the strong presence of red colours in addition to the green. Our cameras will pick up the red tones in particular with far greater sensitivity than us mere humans.

Moonlight and twilights are my favourite additions when chasing auroras because you get a nice blue sky instead of a dark black one. I like this a lot. I even schedule my travels around the moon phases so I get plenty of bold moonlight to work with. There’s kind of an additive effect when you have moonlight, and THAT is when you see the most vibrant green hues, the most strongly. Both in camera and through the eyes.

Compare a moonlit aurora to a totally black night and the difference is quite amazing.

I like both, but for different reasons. Moonlight is great when you want to capture the landscape and bring that into your composition. Dark nights you’re sometimes limited to silhouettes, or doing some “light painting” with special subjects. In general I’m not a huge fan of “light painting”. It looks contrived to me and distracts from the beauty of the stars and the aurora. I prefer a more natural scene.

Capturing auroras is a deeply technical form of photography. It can be very difficult to capture one at all, just to be in the right place at the right time. That’s part of the joy for me, the chase! But elevating from a green blur to a work of art is even more of a challenge. I don’t just want a photo that proves I saw an aurora, I want to make something artistic and beautiful with it. I especially love the connection between the snowy Arctic landscape and the auroras, and how on a dark night the colours of the sky also paint in an otherwise white landscape. The snow picks up the greens and reds.

Green snow, however, can look very odd in compositions. Most people think it looks fake, even though that is exactly what’s happening. So you see, there is always a gap between what the camera sees and what the human eye expects to see. That’s just how it is!

Nights To Remember

The other challenge with aurora is that they don’t always kick off on a big scale. Most aurora events are more gentle. Indeed, most people are not even in the right part of the globe to even see an aurora unless it’s a massive event. Even if you fly to a great place like Tromso, that sits right under the aurora oval, you can’t expect to be guaranteed a good showing of aurora on any given night. You might get lucky and fly in for one night and see it, but some people stay for a week and all they get are clouds or snow. My last tour we saw the lights on seven out of fourteen nights, but mostly through gaps in the cloud. Most of the totally clear skies we had occurred on nights when the aurora wasn’t dancing at all.

But every now and then we get both perfectly clear skies, plus a long and varied aurora event. Those are the nights you will be glad you didn’t sleep in. On the 3rd of March 2024 we had just such a night. A little cloud was flirting with the horizon from the south when we sat down to dinner. At 7:30pm I stepped outside to check for stars (another way of saying, evaluate the cloud cover) and noticed a gentle aurora starting up in the west. There was still some cloud about, but we headed outside and started shooting anyway.

For the next 6 and a half hours we took photos. Some of our team called it a night around 10:30pm. By this time the clouds were totally gone and they felt they’d seen a great show. And they were not wrong! They enjoyed auroras pulsing above their heads and dancing like silk out across the fjord. Those few hours had moments of bright intensity when the green hues really punched through to the human eye. I too felt I had plenty of shots from our cabin, so I drove up the road to try a new location. A new pattern emerged at this stage, as the aurora oval slipped to the south and moved into a higher energy event.

It would be another 5 hours before I got to bed.

With an aurora event of KP2 most of the aurora oval is directly over Tromso. At KP5 it’s a lot further south but also a lot bigger. The great thing about Tromso is that we get super lovely views to shoot in either scenario. As the Level 5 event on March 3 started to build we could see red tones making ribbons to the south-west. I love these patterns, and so does the camera. What seems to the human eye like a pinch of activity in the sky can turn out to be intense and striking reds on the RAW file.

Not only does a digital sensor pick up the red hues better than the human eye, but an ultra-wide 14mm lens changes the perspective too. Instead of being vertical ribbons that pulse across the horizon, the “tall perspective” generated by a 14mm lens makes them look more angular at the edges. It looks as if they move outwards across the landscapes from the middle of the frame, instead of vertically across. It’s a nice effect, but makes composition through the lens quite different to what your eyes are seeing. 14mm pulls in a very very big sky.

What is lost through the camera on these really big nights is scale. That 14mm lens brings in a huge amount of sky, and in some ways can make an aurora seem a little small. And yet, at the same time it fails to bring in the 360° view we experienced – you don’t get any sense of the scale beyond the frame. It simultaneously minimises AND crops these incredible moments. This is one reason I enjoy a timelapse approach, because at least you get a sense of the movement over time. But also note, that timelapse can be misleading to people... They don’t always appreciate that in a 20 second clip you are seeing maybe 20 minutes of aurora dancing. I get asked about this every time I post an aurora timelapse to my social media.

It works great for long and slow events, but looks almost silly for very very fast ones, such as the incredible aurora that burst into action over the skies of Norway on March 3 this year.

Not only was that night just waaaay too fast for my 4 second exposures, but also too bright. I blew out the exposure in some sections, having setup my initial exposure to capture the more delicate red hues earlier in the evening.

One final challenge I want to leave you with is that aurora photography not only demands a fast lens to capture the moment, but a very wide lens. In the Arctic we see them cover 180 degrees of the horizon at a time, stretching from one horizon to the other. Sometimes they are literally lighting up the sky in every direction. So a 24mm lens is not nearly good enough.

Anyway, I talk more about HOW to shoot auroras in special video on my YouTube channel, so if you want to learn a little about how to chase them and setup to capture them, please take a look at that video below :)

– Ewen

Keep Reading

Join Ewen's newsletter for monthly updates on new photography articles and tour offers...Subscribe Here