Change of Perspective

We’ve all seen the Instagram posts of remote forests in Scandinavia, shot with a drone 400ft in the air. Snow on the trees, a winding road and a silver sports car moving through the terrain. It’s a perspective of our planet that was rare until the rise of the drones.

Most of us don’t need to reach 400ft in the air to get a better shot. 40ft will be more than enough to completely rethink our compositions. Good composition is always a matter of changing your perspective, to look for an angle on the scene that steps away from our typical 150cm above the pavement. Photography is all about how you look at the world, and not just when you’re standing tall.

I spent a month in Arctic Norway with a little DJI Spark and immediately fell in love with this new perspective. Standing on the edge of a semi-frozen ocean, with slabs of ice lifted on the tide, I could swing the drone out across the scene and look for the perfect foreground. This little machine, worth under $1000 and sporting a 12MP fixed camera, let me photograph that place in time that I could never reach with my human legs. It was like a flying tripod.

It’s worth mentioning that the size of these aircraft is genuinely small. When unpacked they look both fragile and cumbersome, but the best of them are designed to pack down tight by folding the wings and rotors. You end up being able to stuff the drone, a controller, spare batteries and accessories into a tiny bag the size of a lunch box. You really can take them anywhere with very little fuss.

At present the emphasis on these lightweight drones is video, and stills are kind of an afterthought. I look forward to the day when DJI design a drone like the Mavic Air but with seriously enhanced stills capabilities. A larger sensor, selectable apertures, and maybe take the ‘tripod’ mode a step further to enable slow shutter work. Imagine a 2 second exposure after dusk while waves are crashing over some rock pools, and you’re standing 100 metres away on the sand dunes without risking your safety.

The technology is already present to make this possible today, but the market just hasn’t caught up yet.

"Sunrise and Mist"

Mavic Air / Single Shot 12MP

What’s Up There?

I've often concluded that I’d be a better photographer if I was a foot taller. At my modest height I miss out a few opportunities to gain perspective over a fence or a crowd. But why stop at one foot when 400 are on offer?

I took my Mavic Air up to the Sun Country on the Murray River in Victoria for a commercial shoot. We wanted to capture some of the impressive farming infrastructure of the region, and it turned out the drone was a powerful way to do it. This part of Australia is a critical food bowl, made possible by the irrigation channels that takes water from the Murray River and sends it deep into the landscape. Grains, fodder, fruit, dairy and a other produce rely on the irrigation.

From ground level you can see the landscape move from dust to lush, but from the air the story gains drama and structure. Lines of irrigation networks determine where dairy cows can feed, rolling sprinklers create massive circles in the landscape and solitary paddocks turn green in contrast to the those across the road. These structures are impossible to capture when you’re standing right next to it, you need to gain a little distance and elevation to capture it.

Structure is the key element to successful composition, and droning allows you to access a very big scene and much larger structural elements.

Drone technology also allows you to work a foreground in ways you can’t from the ground. Massive river gums running along a fence line become elements of a much bigger composition as you move a little into the air. Instead of looking up at the trees you can shoot through them, as though they belong to an eye-level perspective. A simple scene such as sunset light reflecting on an irrigation channel can be limited when standing on a river bank, but with a drone you can drift out low across the water and find that perfect spot where grasses rise above the horizon to one side and gum trees create a leading line on the other.

Shooting from a drone is not always a matter of “what’s up there”, but a chance to see “what’s out there”.

Speed and range is the other advantage of the flying tripod. Under the harsh midday sun we saw a broad acre farm under plough. The tractor is nothing like what my grandad used to till his paddocks. This thing was the size of a small house and dragging a complicated rig of tillage devices the size of a tennis court. A plume of dust rose up behind the tractor like a red thunder storm. While watching this scene unfold we put a call into the council offices and confirmed whose farm it was, and within a few minutes we were speaking to the driver of the tractor on his mobile phone. He said gave us the green light to fly over his land and photograph and asked for a copy of the shots.

My drone chose this moment to have a software failure. Eventually rebooting the DJI app sorted the glitch and I had barely a few minutes remaining before the "tractor of doom” finished his last run and dropped a cloud of dust on top of us. The drone flew out at 40kph and was quickly in position to circle around the scene, about half a kilometre away at that time. I had enough air speed to lock down several vantage points of the tractor, the tiller and the dust cloud. Some scenes were backlit, some with cross lighting and some from lower down with the cloud rising high above.

My flight log shows the total flight time for that shoot was just 8 minutes. But it was the right 8 minutes and the results were sensational.

"Tillage and Dust"

Mavic Air / single shot 12MP

You Can Tube

If you want to kill a few hours one rainy afternoon just go onto YouTube and search for “my drone didn’t come back”. It’s hilarious and painful and will make you ponder how many lithium batteries are sitting at the bottom of shallow oceans causing toxic pollution to local marine life.

I loved exploring the coastline of Arctic Norway with a drone recently, but it turns out I should have spent just a little bit more. It only captures JPG instead of RAW files and shoots 1080p video instead of 4K. The new Mavic Air upgrades these two specifications. Image capture was not the big issue with the Spark however, the main problem is they have a tendency to go rogue and not come back.

The DJI Spark is amazingly capable, but evidently critically flawed in the cold air and northerly latitudes of the Arctic. The GPS routinely would drop in and out. Most of the time the drone would cope OK with the GPS flipping, but every now and then it would take off in a random direction while we watch it fleeing at max speed away from us. Sometimes it was retrievable through the controls, sometimes not.

One of my travel companions had the far more capable Mavic Pro and even he experienced this event a few times during the journey. Our Spark failed to come back day, having gone rogue before spinning into a chaotic panic. We watched helplessly on the screen of my smartphone until the FPV froze and the signal lost. Our drone did not come back. The last reported GPS coordinates proved insufficient to locate the fallen aircraft.

One of the major differences between the Spark and Mavic Pro is the wireless signal between controller and the aircraft. Instead of an RF signal that can cover 7kms of range, the Spark uses a modified WiFi technology that was more susceptible to interference and temperature. The new Mavic Air uses an improved version of that WiFi connection, and I’ve enjoyed some seriously good range with it when shooting in the outback. To date my Mavic Air has reliably come back every time and I look forward to testing in the Arctic winter again next year.

"DJI Spark"

Not recommended in the Arctic

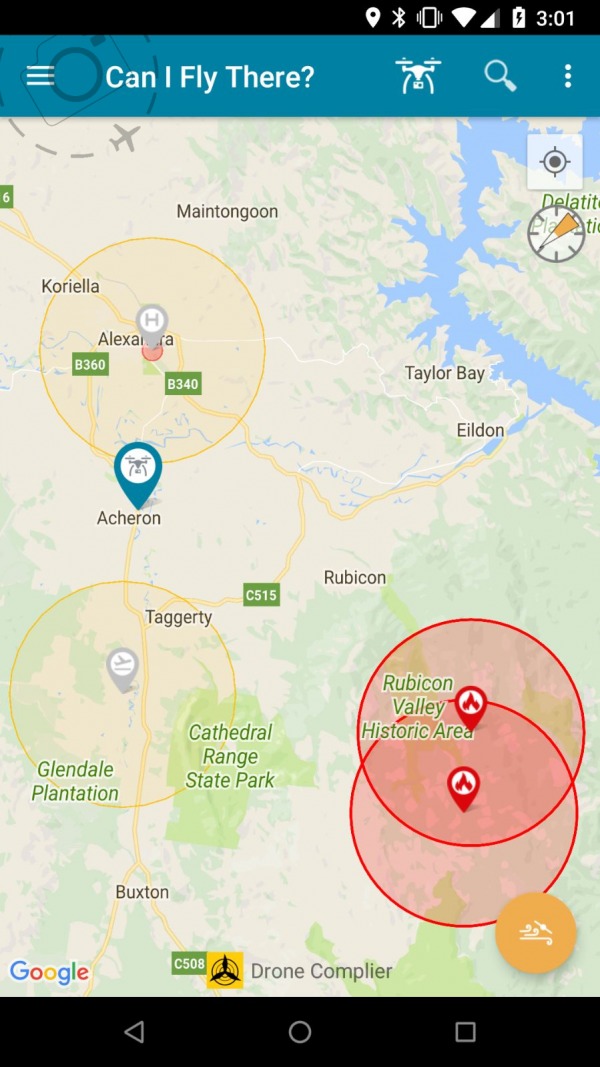

Commercial Compliance

In Australia the use of drones is well regulated. If your drone is under 2kg, such as the Mavic series, then you can operate without full certification but must adhere to a set of guidelines. Commercial work is also permitted with these smaller drones but you need to register with CASA and lodge basic activity reports before flying.

The guidelines are sensible ones. Don’t fly too close to people. Don’t fly near airstrips and helipads. Don’t fly near an emergency situation. If you want to go beyond these restrictions, or fly a heavier drone, then you need to invest a fair bit of time and money to earn certification with CASA.

If you want to fly in a national park, however, then chances are you will be frustrated. Most states have decided to simply ban drones from parks entirely, recreational or otherwise. Without that full certification from CASA you won’t be allowed to apply for commercial filming permits even with a small aircraft like the Spark. It’s not hard to see why elementary restrictions are in place, as our parks would easily end up filled with annoying dronists buzzing walkers and wildlife. I have met dozens of drone owners who brag about ignoring restrictions, seemingly ignorant that this makes them look like idiots instead of heroes.

At the moment the attitude from parks bodies towards professionals does seem very heavy handed, in shutting the door to genuine photographers who want to apply for a permit. Most require a level of certification that goes beyond the CASA guidelines. I would argue they have over-reacted and are choosing the path of least effort by just saying “no” to reasonable requests. There is room for improvement where permits can be used in conjunction with established CASA restrictions.

And a word of warning to those who say, “No one will catch you, who’s going to see you out there anyway?” If the objective of your droning is to have great content to share online or with your clients then all the evidence for prosecution will be readily available online. Reporting of illegal drone activity is a thing and authorities in many countries are actively keeping an eye on hashtags. So just don’t be a douche - there are lots of good shots to be had out there without breaking the rules.

Air Time

The key to cultivating your creative skill with drones is to practice and practice and practice. It’s not just a case of pop the drone in the air and expect to get an award winning shot. Being 40 to 400ft up in the sky is not the only requirement for great photography. You need to spend time in the air and get familiar with how to see the world from this new perspective. Everything looks different to how we typically see the landscape, so you’re cultivating a new vision as well as new skills.

You’re also cultivating an appreciation for the limitations of the technology. Simple things such as how long the drone will fly on a single charge, how high wind speeds interfere with your gimbal, communication glitches when the drone decides it wont take off or gets twisted up trying to find a clear WiFi channel. They don’t always work straight out of the box. You can be standing on the edge of a quiet farm road watching a magnificent sunset and for whatever reason the drone decides it’s compass isn’t ready for takeoff, or there’s too much interference from metallic material in the ground, or something else.

Just unpacking these smaller drones and unfolding them for flight requires a degree of focus. It can't be rushed or you overlook things like removing the gimbal lock and end up having to relaunch and lose even more vital minutes.

Sometimes you realise you can’t take off because you’re in the middle of a restricted zone. The DJI app is very good at tracking no-fly zones, but also the CASA drone app will give you nuanced information on where the local aircraft might be operating. Even if the apps say you’re good to fly and the drone is happy to launch, you still need to be aware of any potential dangers such as powerlines and people wandering through the location. I was about to take off on a quiet river bank when out of nowhere a group of cyclists turned up, so had to sit and wait for them to roll off again.

You can’t fly within 30m of people as part of the CASA restrictions.

All of this we put in the category of “Situational Awareness”. You’re not just composing a shoot with the flying tripod, you’re operating a complex bit of technology that is nowhere near perfect.

"First Light and Mist"

Mavic Air / 9 frame Horizontal Pano

35MP stitched with Autopano

Wishlist

I’m old enough to remember that moment in history when digital SLR technology moved from a cool idea to a serious commercial advantage. 12MP RAW files were the tipping point. We’re at that point again now with drones, and models like the Mavic Air cost a hell of a lot less than my first 12MP DSLR. I’m seriously excited about what lies ahead in the next few years. Do not ignore this space. High resolution sensors with fixed wide angle lenses, dangling from a quad-copter, could change the way you think about photography.

It’s an entirely new creative frontier for regular stills photographers. It’s not just for bloggers and vloggers or high adrenalin extroverts who need a “follow me selfie” as they mountain bike down the side of a volcano.

The restrictions within national parks is one I really do hope can be improved in due course. I simple permit system that lets amateurs and professionals conduct non-intrusive drone photography would offer a chance for many photographers to share even greater inspirational images of our most treasured wild places. We already have excellent app technology coupled with the drones, and it’s a simple step to connect flight logs to the permitted activities and ensure sensible and safe use of flying tripods.

In the meantime, we live in a wide brown land with sheep stations the size of small European nations. There are wide open spaces away from the national parks where you can explore the world from above. I can definitely recommend the Mavic Air for this task, delivering an impressive dynamic range from the RAW files and stunning flight performance in all aspects. The fact that it also happens to shoot 4K video is a nice bonus too :)

"Irrigation Channel at Dusk"

Mavic Air / single shot 12MP

PanoDrones

I want to finish this feature with a closer look at shooting panoramas from a drone. This is one way you can build very good resolution from a very modest drone. I first dabbled in the panorama mode of the Mavic Air because I was hitting scenes that needed a wider perspective than the 25mm lens it carries. I do this a lot with my regular photography, and have a smooth workflow for taking the frames and putting them together with refined processing.

One of the side benefits of shooting a pano is you get bigger files at the other end of the process. A simple 3-frame vertical panoramic on my Mavic Air can generate a 30MP frame that any publisher can use on the cover of a glossy magazine. That’s a really big factor when evaluating how commercially useful a 12MP drone is for stills photography.

It’s more work to think about your droning in terms of panoramas. You’re looking for potential scenes through the viewport of your smartphones, you’re sliding the gimbal up and down to scan the landscape, and you’re working with a wider field of view than the 25mm lens on board. Not every scene will work well. Shooting panos with such a wide lens has it’s own issues too, making it tricky to avoid excessive distortion on foreground elements that are very close. The fact that we’re limited to flying to 120m of altitude plays into the foreground distortion issue quite a bit when shooting vertical panos.

A few drones, such as the Mavic Pro, can also flip the camera into portrait mode and hence take better resolution with better overlaps when shooting a horizontal panorama. That’s a great advantage when shooting traditional panos, and the software that drives your Mavic Pro makes it easy to slip into panoramic shooting modes and let the aircraft do most of the hard work to execute the frames.

I’m very excited about what can be achieved with the panoramic modes on my little aircraft. It’s a big step towards ticking off my wishlist for the perfect flying tripod. There’s a lot of buzz about capturing “little planets” and other fun gimmicks. But beneath the bubble of trending social media lies some seriously useful hardware and the opportunity to capture beautiful stills images that until now we could only imagine.

In fact the greatest shift in your photography once you own a drone is that you do start to imagine scenes that you probably never would have imagined before.

"Sunrise over the Goulburn River"

Mavic Air / 9 frame Horizontal Pano

32MP stitched with Autopano

Keep Reading

Join Ewen's newsletter for monthly updates on new photography articles and tour offers...Subscribe Here